The Attentional Blink and Repetition Blindness

Introduction

In the activity on the rapid serial visual presentation (RSVP) paradigm we explored some ways in which attention can be deployed to rapidly changing real-world scenes. In this activity, we will use the RSVP paradigm with much simpler and more well-controlled stimuli to determine how easily observers can detect the presence of a letter or number in an RSVP stream.

Click on the white square at left to see an RSVP sequence of 20 letters.

Now click the white square again to see another sequence, and try to determine whether there is an A or a B in the sequence. With a little practice, you should be able to detect the A/B fairly easily at this speed of presentation. Try it as many times as you like.

Two particularly interesting phenomena uncovered with the RSVP paradigm are the attentional blink and repetition blindness. In the attentional blink, observers have difficulty detecting a second target for a short time after detecting the first target. In repetition blindness, observers tend not to notice that a letter or word they are looking for has been repeated. Both phenomena point to limits on the temporal resolution of our attentional systems.

Instructions

Click the links at left to try an attentional blink or repetition blindness experiment yourself and read more about the phenomena.

Attentional Blink Experiment

In an attentional blink (AB) experiment, observers are asked to detect two targets, with the second target (“T2”) coming 100–600 ms after the first target (“T1”) in the sequence. The “blink” occurs about 200–300 ms after T1 is detected. If T2 appears within this time window, observers typically do not detect it.

In this section of the experiment, you will see what it is like to participate in an AB experiment. When you click on the white square at left, you will see an RSVP sequence of 20 letters. T1 will be either an A or a B. T2 will be either a Y or a Z, and will appear somewhere in the sequence after T1.

Your task is to watch the sequence, then click either A or B in the left-hand black rectangle below to indicate what you think T1 was, then click either Y or Z to make a guess about T2.

Click in the white square at any time to start a trial.

If you’re not sure about one of the targets but you think you know what it was, go ahead and take a guess. If you have no idea about one or the other of the targets, click the ? instead of a letter in the appropriate black rectangle.

[See below for the instructions presented in a different way.]

In the activity introduction, the RSVP sequences were shown at a rate of one letter every 200 ms (i.e., 5 Hertz, or 5 letters/second).* For the experiments, this rate will be sped up to 10 Hz. If you’re having a lot trouble detecting T1, the program will automatically slow the sequences down a bit.

*Web browsers are not the ideal environment for running psychophysical experiments, and the letters in our RSVP sequences may sometimes be delayed by more or less than the amount of time we’re aiming for.

Instructions

Your task in each trial of the Attentional Blink experiment is to monitor the RSVP sequence for two targets, T1 and T2. T1 will be either an A or a B, and T2 will be a Y or a Z. The sequence of actions for each trial are as follows:

- Click the white square to begin the trial. Fixate on the cross that will appear in the center of the screen.

- Try to detect T1 and T2.

- Once the RSVP sequence is completed, first click on either the A or the B in the small black rectangle below the white screen. If you have absolutely no idea whether T1 was A or B, click the ? in between the two letters. But if you have even an inkling of what T1 was, take a guess.

- Now click on either the Y or the Z in the other small black rectangle. Again, if you have absolutely no idea about T2, click the ? between the two letters, but take a guess if possible.

- Once you've made both responses, the program will show you the entire sequence that you just saw and will present the results of the experiment so far. From this results screen, you can reset the results of the experiment if you want to start over.

- If you are distracted during the trial and look away, don't make a response; just click the white screen again and a new sequence will appear.

Attentional Blink Control Experiment

Imagine that you are the first scientist to try this experiment. You find that subjects are particularly poor at detecting T2 when it follows 2–3 letters after T1. You would like to argue that subjects have difficulty detecting T2 because their attention was just focused on detecting T1. But it might just be that Y/Z is harder to detect than A/B. Or it might be that letters later in the sequence are harder to detect than letters earlier in the sequence. Or, there might be some other alternative explanation. (Can you think of any others?)

Many psychologists like nothing more than bursting other psychologists’ bubbles by pointing out such potential confounds in experiments. So to protect yourself, you would want to run a control experiment to counter these potential objections. In this case, the control experiment is particularly easy: Just have subjects detect the Y or Z without worrying about the initial A or B. This task should be equally easy regardless of the lag between the A/B and the Y/Z.

Try it yourself. Click in the white square at any time to start a trial.

Now your only task is to detect the Y or Z. Don’t worry about whether there’s an A or a B in the sequence.

See below for detailed instructions.

Instructions

Your task in each trial of the Control experiment is to monitor the RSVP sequence for a single target: either a Y or a Z. An A or a B will also occur somewhere in the sequence, as in the attentional blink experiment, but you should not pay any attention to the A/B. Just look for the Y or Z. The sequence of actions for each trial are as follows:

- Click the white square to begin the trial.

- Fixate on the cross that will appear in the center of the screen.

- Try to detect the Y or Z.

- Once the RSVP sequence is completed, click on either the Y or the Z in the small black rectangle below the white screen. If you have absolutely no idea whether the target was a Y or a Z, click the ? between the two letters. But if you have even an inkling of what the target was, take a guess.

- Once you've made your response, the program will show you the entire sequence that you just saw and will present the results of the experiment so far (note that your results for the control experiment are kept separately from your results for the attentional blink experiment). From this results screen, you can reset the results of the experiment if you want to start over.

- If you are distracted during the trial and look away, don't make a response; just click the white screen again and a new sequence will appear.

More About the Attentional Blink

The graph at left shows a typical response pattern for our version of the attentional blink (AB) task. The x-axis represents the time between when T1 and T2 appeared. The y-axis represents the percent correct responses at identifying T2, given that T1 was correctly identified. As you can see, performance is fairly good at lags 1, 5, and 6 (that is, when T2 is the first, fifth, or sixth letter to appear after T1), but close to chance (50 percent) at lags 2, 3, and 4. Note that we are only concerned with trials in which T1 is accurately reported, because if T1 is missed, the AB task is essentially identical to the control task, where T1 was to be ignored. (How close are your results to this graph? You will probably have to do at least several dozen trials before a reliable pattern emerges in your data.)

One explanation of the AB phenomenon is that there are two separate attentional processes involved in the task. The first process monitors the RSVP sequence and identifies each letter as it goes by. The second process comes into play when you actually have to do something (e.g., make a decision about whether there is an A or a B in the sequence and commit that item to memory).

The second process, according to this explanation, takes resources away from the first process. So if you see an A and devote some attentional energy to noting that it is T1, there will be a small amount of time during which there are not enough attentional resources left over to detect T2. After 300 ms or so, resources can be shifted back into the first process, allowing T2 to be detected accurately at lags of five or six letters.

So why is performance so good at lag 1? It may be that two consecutive letters can be responded to simultaneously. In other words, the second process can grab T1 and T2 together if they occur next to each other in the sequence, so both targets can be accurately reported. But when at least one letter intervenes between T1 and T2, the attentional blink comes into effect and T2 may be difficult to detect.

Repetition Blindness Experiment

In a typical repetition blindness (RB) experiment, subjects monitor an RSVP stream of words and try to detect any that are repeated. If a word is repeated shortly after its first appearance, observers typically do not notice as frequently as if the word is repeated later on.

You can experience what it is like to participate in an RB experiment: Click on the white square at left and try to detect the repeated word. After the RSVP sequence is finished, you will have a choice of four words that appeared in the sequence. Click on the one that you thought was repeated. If you are not sure, click the ? instead of a word.

Click on the white square at any time to start a trial.

More About Repetition Blindness

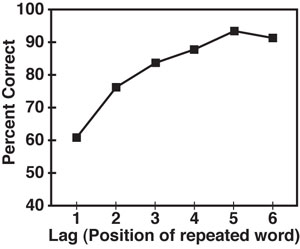

On the top left is a graph depicting the typical data pattern for a repetition blindness (RB) task such as the one here. When a word is repeated very soon after it first appears, observers are much less likely to detect it. However, the longer before the repetition of the word, the more likely the repetition will be detected.

You may notice some differences between the RB data depicted here and the data from the AB experiment. In RB, lag 1 items are usually the worst detected whereas there is typically no deficit for lag 1 in AB. In AB, lag 2 typically yields the worst performance in a classic U-shaped pattern. In RB, lag 1 is the worst and then performance steadily improves over time.

One explanation of RB is that it represents a failure of visual attention to register that two instances of an item are actually two separate entities. In the literature, a particular item or event is often referred to as a token. RB is thought to be a failure of token individuation. That is, when two tokens appear in rapid succession, you have a difficult time noticing that they are two different events, even if there has been another token (e.g., a word) in between!

For instance, take a look at the sentence in the triangle below the data graph. Do you notice anything strange about the sentence? The word “the” is repeated. If you did not notice the repeated word, you have experienced the phenomenon of repetition blindness!

Repetition Blindness Experiment

Watch the sequence of letters carefully, then click A or B to indicate what you think T1 was, and Y or Z to indicate T2. If you're not sure, just take guesses.

Your results so far will be shown once the trial is done.

Repetition Blindness Control Experiment

Watch the sequence of letters carefully, then click Y or Z. If you're not sure, which letter you saw, just take a guess.

Your results so far will be shown once the trial is done.

Repetition Blindness Experiment

Click on the white square at right and try to detect the repeated word. After the RSVP sequence is finished, you will have a choice of four words that appeared in the sequence. Click on the one that you thought was repeated. If you are not sure, click the ? instead of a word.