Essay 1.1 Senses of Reality Through the Ages

“What is real? How do you define real? If you’re talking about what you can feel, what you can smell, what you can taste and see, then real is simply electrical signals interpreted by your brain. This is the world that you know.” This is Morpheus’s answer to Neo in the 1999 movie The Matrix, starring Laurence Fishburne and Keanu Reeves (Image 1.1).

Image 1.1 In the movie The Matrix, Morpheus (left) talks to Neo about the nature of reality. (© Warner Brothers)

As you may know or suspect, people have asked these questions for a very long time, perhaps as long as humans have existed. The Matrix was actually inspired by “The Allegory of the Cave” in Plato’s Republic, written in about 380 BCE. In this story, Plato (428–348 or 347 BCE) (Image 1.2) compares our ordinary sense of reality to that of prisoners in a cave (Image 1.3). He describes prisoners tethered together since childhood, able to see only the wall in front of them. Far behind them is a fire, and between the fire and the backs of the prisoners are men, sometimes talking and sometimes not, carrying statues and other objects. All the prisoners ever see are shadows on the wall in front of them. This is the prisoners’ complete reality.

Image 1.2 Plato lived during the golden age of Greece, a time when philosophers often were celebrities. Plato was an especially colorful person. Naked and covered in oil, he competed in the original Olympic Games. (He was younger then!)

Image 1.3 Prisoners in Plato’s imaginary cave could learn about their world only from shadows on and echoes from the wall in front of them.

Plato paints this imaginary picture to emphasize how critically our conception of reality depends on what we can learn about the world through our senses. You do not have to think of yourself as a prisoner tied up in front of a wall, but you should appreciate the fact that almost everything you think is true about the world around you depends on what you can learn through your eyes, ears, nose, tongue, and skin.

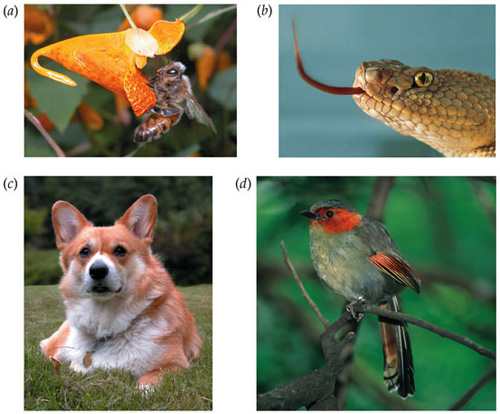

Perception and your sense of reality are the products of evolution. Senses have evolved to help us act in ways that encourage our survival (Image 1.4). If you were an animal moving through the environment, you would be at a great disadvantage if you could not use eyes or ears to gain information about the world around you. In general, our senses have evolved to match just the sorts of energy in the environment that are most important for our survival. For example, human vision is restricted to light in a very narrow band of the electromagnetic energy closely related to the energy that reaches the surface of Earth from the sun.

Image 1.4 Sensory systems evolved to guide activity that is essential to survival. The Venus flytrap is one of the rare plants that can sense vibration in order to move quickly to capture prey.

Humans sense a subset of the energy that surrounds us (Image 1.5). Other animals can sense energies that we cannot. Bees, for example, can see ultraviolet light that reveals patterns in flowers otherwise invisible to us. Using a special organ in front of each eye (see Image 1.5b), rattlesnakes and other pit vipers sense infrared energy that we cannot see, and they use this sense to locate their prey. Dogs and cats, not to mention bats, can hear sounds with higher frequencies than we can hear. Many birds, turtles, and amphibians are able to use magnetic fields to navigate. Elephants can hear very low-frequency sounds, and they may use this ability to communicate over long distances. As you sit quietly reading this essay, you are being bombarded by many types of energy to which you are not sensitive. Although not as limited as the imaginary case of Plato’s prisoners in a cave, your understanding of reality, and even your sense of imagination, is restricted to those things that you can perceive through your senses.

Image 1.5 Our senses are capable of gaining information about only a tiny fraction of the energy and events that occur all around us. Honeybees (a), snakes (b), dogs (c), and birds (d) are able to sense a variety of stimuli that humans cannot.

More than two millennia before the field of psychology existed and the first formal perception experiments were conducted, philosophers pondered the ways in which our perception of reality depends on our sensory experiences. Heraclitus (about 540–480 BCE), a very influential early Greek philosopher, lived about a century before Plato. He is best known for his famous statement, “You can never step into the same river twice.” Heraclitus used this metaphor to stress his view that everything is always changing. Because the river flows continually past, the water a person steps into once is not the same water the next time. The same is true of our own perceptual experiences. No two experiences can ever be identical, because experiencing the first event changes the way we experience the same event a second time.

Several important facts follow from Heraclitus’s simple observation. Perception does not depend only on energy and events that change in the world. Perception also depends on the qualities of the perceiver. Even when exactly the same event happens twice, it will not be perceived the same way twice, because the perceiver has changed following the first event. Experience with the world around us plays a very large role in the way perception works, beginning very early in life. Even before birth, the sounds that the fetus hears will shape later listening. The structure of the environment around us, including cultural differences such as the speech and music we hear, molds the way perception works.

The idea that the world is continually changing is important for perception in another way. Perceptual systems are acutely sensitive to change. In many different ways, every sense highlights and emphasizes changes around us. In fact, we tend to be quite unaware of things in our environment that do not change. Things that move draw our attention. Ambulance sirens constantly change in pitch so that drivers are more likely to notice them. The flip side is that perception quickly comes to ignore anything that stays the same for very long. The general mechanism is known as adaptation. All of our senses adapt to constant stimulation. For example, when we first arrive at someone’s house, we may quickly detect a strong odor—perhaps mothballs, perfume, or dinner. Even though the odor is readily apparent, the olfactory (smell) system soon adapts to it, and we no longer notice it as much, if at all. Adaptation and other perceptual processes render things that are steady or predictable in the environment much less salient than things that are changing.

Unlike his contemporary Plato, the Greek philosopher Democritus (about 460–370 BCE) had almost complete trust in the senses. This trust arose from his radical idea that the world is made up of atoms that collide with one another. Of course, Democritus couldn’t see these. It would be 2000 years before even simple microscopes were invented to visualize single-cell organisms. Nevertheless, he believed that sensations are caused by atoms leaving objects and making contact with our sense organs. For Democritus, this meant that our senses should be trusted because perception is the result of the physical interaction between the world and our bodies. He thought that the most reliable senses were those that detect the weight or texture of objects, because we are in direct contact with things when we make judgments of weight and texture. Democritus held that all the other qualities were secondary because they have to involve atoms moving from the object to interact with atoms of the perceiver.

Despite being way ahead of his time in suggesting the existence of atoms, Democritus did get some things wrong. It is usually light reflected from an object that allows us to see the object; there are no atomic films peeling off of visible objects. When we hear speech, our ears are detecting sound pressure waves, not atoms from a person’s mouth. Taste and olfaction, our sense of smell, come closest to Democritus’s theory. In those chemical senses, we detect molecules (not isolated atoms, but close enough) binding to receptors on the tongue or deep inside the nose.

Democritus made the distinction between primary qualities that can be directly perceived (weight, texture) and secondary qualities that require interaction between atoms from objects and atoms in the perceiver. We don’t use these terms, but we honor something like this distinction when we talk about sensation and perception. The distinction between sensation and perception is not always clear. When we talk about sensation, however, we will be concerned with the ways that information from the world is picked up by sense organs and detected by the owners of those organs.

Perception deals with the interpretation of those signals. What does a specific pattern of activity in our nervous system tell us about the world outside? Perception is likely to depend more on experience than sensory reception does. That said, a division between sensation and perception will not be clearly marked. It can’t really be done. If you see a simple patch of red light in the dark, your simple sensation of red will coexist with a perception of red, colored by all the other reds you have ever experienced.

Nativism and Empiricism

Plato used “The Allegory of the Cave” to emphasize limitations on what we can know about reality from our senses. He went on to claim that the truest sense of reality comes from deep within people’s minds and souls. Plato thought there were two worlds: the world of Opinion and the world of Knowledge. The world of Opinion was taken to be incomplete because it is limited by information conveyed to us through our senses. This is all that Plato’s prisoners could know. In contrast, Plato thought that real Truth (with a capital T) is found in the world of Knowledge. The world of Knowledge is where souls reside, and according to Plato, each soul is joined to a body for a lifetime. This idea that certain mental abilities must be innate is known as nativism.

René Descartes

Long after Plato, nativist René Descartes (1596–1650) (Image 1.6) came to a similar conclusion concerning the relationship between mind and body. He argued that only humans have mind. In his view, similarities between humans and animals would be restricted to body structures and functions. For present purposes, we are interested in Descartes’s dualist view of the mind. He considered the mind to be quite separate from the body. For Descartes, the mind is unextended (does not take up space) and has no substance. It is distinct from the body and survives the death of the body (like a soul). Like Plato, Descartes thought that all true ideas must come from the mind, and he did not trust his senses. Unlike Plato, who competed in ancient Olympic Games, Descartes was said to have been a very lazy young man. The monks at his church school used to throw buckets of water on young René to get him out of bed, where he would spend much time awake but pondering. Perhaps his attraction to the sedentary life was related to his most famous philosophical statement: Cogito ergo sum (“I think, therefore I am”). By this, Descartes asserts that his thinking mind (and not experiences) defines and proves his existence.

Image 1.6 René Descartes was one of the most important philosophers of all time, and he was equally famous as a physicist, physiologist, and mathematician.

Because of Descartes’ philosophy of body and mind, he claimed that animals were in most ways very similar to humans. His only distinction between humans and animals was that humans have minds and souls, so he believed that studying animals was a good way to learn about the material parts of humans. Descartes was very interested in learning more about the inner structure of bodies and brains, and he actually dissected both. He proposed that animal spirits (which were matter, not mind—somewhat like mineral spirits or alcoholic beverages) enter the brain and exit through pores that guide this fluid through nerves to muscles. In effect, he thought of animals as hydraulic machines and humans as machines with the addition of mind and soul.

Thus far, the distinction between mind and body might seem sensible and consistent with the way you think about yourself and humans in general. People typically think of themselves as having a mind that takes in information about the world through the senses before choosing to act in particular ways on the basis of that information. The logical alternative to dualism is that humans, and the rest of the universe for that matter, are made up of only one kind of stuff. This position is known as monism. Among monists, those who hold that everything is matter embrace materialism, which is referred to as physicalism by contemporary philosophers. Those who hold that everything is mind embrace mentalism.

However natural a separation between mind and body may seem, there is a problem with mind–body dualism: how does that mind, having no substance, weighing nothing, and occupying no space, have any effect on the physical body? Philosophers continue to struggle with this problem, and most believe in physicalism much like psychologists do.

Empiricism

You may ask what, if anything, all this has to do with learning about perception. As it turns out, much of the development of thinking about perception grew out of questions concerning the relationship between mind and body. The British philosopher Thomas Hobbes (1588–1679) (Image 1.7) took this problem quite seriously and concluded that, for him, the only sensible answer is that only matter exists. Hobbes rejected the concept of spirit, or God, because such things would have no matter or bodies. Instead, he provided a mechanical model of humans and of society more broadly. In Hobbes’s universe of matter alone, he argued that all knowledge must arise from the senses: “For there is no conception in a man’s mind, which hath not at first, totally, or in parts, been begotten upon the organs of the Sense” (Hobbes, 1651/1914, p. 3). In short, Hobbes rejected the nativist ideas of Plato and Descartes. Instead, Hobbes was an empiricist, meaning that his model of human nature relies entirely on experience.

Image 1.7 Thomas Hobbes believed that everything that could ever be known or even imagined had to be learned through the senses.

Because Hobbes viewed all mental activity as a consequence of experience, he had what may seem an especially dim view of memory, thinking, and imagination: he thought memories were simply sensory experiences that were old and faded. And thinking was little more than connections between memories. Because there would be nothing to the mind other than sensory experiences, imagination was not thought to be creative at all. Instead, Hobbes wrote that imagination “is nothing but decaying sense” (Hobbes, 1651/1914, p. 5).

John Locke (1632–1704) (Image 1.8), another British philosopher, provided us with empiricism’s most vivid image: that of the newborn mind as a tabula rasa, or “blank slate,” on which experience writes. Like Hobbes, Locke suggested that all ideas must be created through experience. He believed that our rich experiences of the world around us, and our subsequent ideas about that world, all begin when the simple stimulation of our sense organs (eyes, ears, skin, nose, tongue) is conveyed to the mind. These first sensory impressions were called “simple ideas,” and they may be thought of as primary qualities. Because they are simple and cannot be divided further, these sensory impressions are not the same as the experiences that we normally have with the world. For example, when we perceive a cat, our experience is the combination of different simple qualities, such as seeing the color, hearing the purr, feeling the fur, and smelling Meow Mix. The combination of these simple qualities comes only through experience.

Image 1.8 John Locke sought to explain how all thoughts, even complex ones, could be constructed from experience with a collection of sensations.

Locke’s ideas led to a famous exchange with the Irish scientist William Molyneux. Locke and Molyneux agreed that people who were born without sight but later gained the ability to see would not be able to recognize objects that they had previously only touched or heard because they had never seen the world with their eyes. To test this speculation, one would need to restore sight to the blind. This doesn’t happen frequently. In some cases, however, the optics of the eye are opaque or translucent, and surgery can be performed to remove tissue and restore vision. In the days before anesthesia, operations on such patients were very rare.

Today, the answer to Molyneux’s question is becoming clearer. Studies undertaken as part of Project Prakash—a humanitarian and scientific effort to treat congenitally blind children in India and also study their subsequent visual recovery (http://web.mit.edu/bcs/sinha/prakash.html) demonstrate that Locke and Molyneux had it right. Upon gaining sight for the first time, previously blind patients cannot visually match an object to a sample they were touching at the time (Held et al, 2011). The good news, however, is that mapping between new visual abilities and other senses is learned quite rapidly.

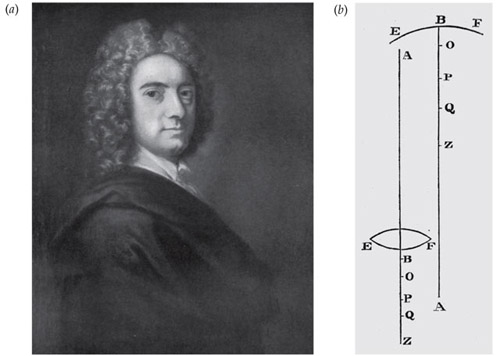

The city of Berkeley, California, is named after another famous philosopher who was quite attracted to what was then the New World. Irishman George Berkeley (1685–1753) (pronounced “Barkley”) (Image 1.9a) traveled to Newport, Rhode Island, with hopes of starting a college. Young Berkeley did not receive the money he needed, so he headed home and became a bishop in Ireland. Berkeley thought a lot about perception, and about what perception tells us about the way minds operate. During the early 1700s, Berkeley was also inspired by Molyneux’s questions about blind people being able to see again, and he was led to think seriously about how vision works. He began by asking the seemingly simple question of how we know how near or far objects are from us when we see them. Berkeley (1837 [1709]) was on the right track when he argued that no single strategy will always tell us how distant something is (Figure 1.9b). Instead, observers must use several visual cues to perceive distance. Berkeley concluded that we learn how to perceive distance by experiencing many objects and scenes in the world. When we do this, we learn how different visual cues change together at different distances. Through experience we learn how to use multiple visual cues to arrive at a pretty good estimate of where things are.

Image 1.9 Berkeley’s exploration of how vision works. (a) George Berkeley studied ways in which perception, such as perception of distance, is limited by the information available to us through our eyes. Nevertheless, he was convinced that everything we know must come from our sensory experience, no matter how limited it may be. (b) One of Berkeley’s own drawings illustrating how difficult it is to know the distance of an object on the basis of light entering the eyes. (From Berkeley, 1837 [1709].)

When Berkeley thought about perceiving distance, as well as seeing other parts of our visual world, he became convinced that the most important part of perception was experience with the world. Like Plato, Berkeley appreciated that there are limits on perception, no matter how much experience the perceiver has. Like Hobbes and Locke, in contrast, Berkeley concluded that all of our knowledge about the world must come from experience, no matter how limited perception may be. So strong was Berkeley’s conviction, that he disagreed with Descartes’s “I think, therefore I am,” stating instead, Esse est percipi (“To be is to be perceived”)—the world exists only to the extent that it is perceived. You’ve no doubt heard the question, “If a tree fell in the forest and no one was there to hear it, did it make a sound?” For Berkeley, if no one was there to hear (or see) it, the tree never existed in the first place.

With all this discussion about the limitations of perception, you may be asking yourself why the world seems so real. If we can see and hear only some wavelengths, and dimensions like size and distance are interpretations by the brain, why does the world around us seem so real and structured? David Hume (1711–1776) (Image 1.10), perhaps the most significant of the British empiricists, offered a simple explanation based on the distinction between reliability and validity. Reliability refers to the consistency of measurements. Do we get pretty much the same answer every time? Validity refers to the relationship of the measurement to what is measured. A measure of your height can be very reliable, but it is not a valid measure of your performance in class. One may hope that exam grades are a more valid measure.

Image 1.10 Dave Hume believed that we perceive the world as real because our senses are highly reliable, even if limitations on perception do not permit our perception to be completely valid.

Hume argued that the world, as portrayed through our senses, seems very real because perception is highly reliable. Given the same state of affairs in the world, our senses deliver the same answers. Luckily, evolution has not permitted these answers to vary much from what is necessary to guide actions that encourage our survival. The senses do their job the same way nearly all the time, so they reliably inform our activities in the world.

We hope you enjoyed this brief review of 2,500 years of thinking about senses and reality prior to the scientific findings you will learn about in your textbook. As you will see, many of these old ideas are as relevant today as they were when first considered by legendary thinkers of our distant past.

Glossary Terms

- empiricism

- The idea that experience from the senses is the only source of knowledge.

- mentalism

- The idea that the mind is the true reality and objects exist only as aspects of the mind’s awareness. Mentalism is a type of monism.

- mind–body dualism

- Originated by René Descartes, the idea positing the existence of two distinct principles of being in the universe: spirit/soul and matter/body.

- monism

- The idea that mind and matter are formed from, or reducible to, a single ultimate substance or principle of being.

- nativism

- The idea that the mind produces ideas that are not derived from external sources, and that we have abilities that are innate and not learned.

- sensory transducer

- A receptor that converts physical energy from the environment into neural activity.