Essay 2.3 Clinical Case: The Man Who Couldn’t Read

Imagine not being able to read because you couldn’t see well enough. What follows is the sad story of a man in this very predicament. This healthy 72-year-old loved to read. He read the newspaper religiously every day (especially Sundays), and he read approximately a book a week. But he began to notice that reading was becoming difficult. There seemed to be a blurred spot in the center of his vision that was becoming gradually worse, making it difficult for him to read and to recognize faces (Image 1). Reading was a bit better under bright lights, but reading the paper indoors, or a menu in a dimly lit restaurant, was becoming progressively more difficult. He also noticed a small—but growing—blind spot in the middle of his field of vision.

Image 1 The panel on the left illustrates the way the right-hand panel might look to someone with age-related macular degeneration (AMD). (From National Eye Institute, 2010.)

A visit to the eye doctor confirmed that the man had age-related macular degeneration (AMD). AMD is a disease associated with aging that affects the macula, the central part of the retina that has a high concentration of cones. The fovea is a small pit near the center of this area that contains the highest concentration of cones. AMD is the leading cause of visual loss among the elderly in the United States, and it gradually destroys sharp central vision, making it difficult to read, drive, and recognize faces. The man’s blind spot in the middle of his visual field, also known as a scotoma, is a consequence of the loss of cones in the macula. You can experience a temporary foveal scotoma in Activity 2.7 Simulated Scotoma.

AMD comes in two flavors: wet and dry. In wet AMD, abnormal blood vessels behind the retina start to grow under the macula, and because they are fragile, they leak blood and fluid. The blood and fluid raise the macula, resulting in a rapid loss of central vision. Because the macula is displaced, straight lines may look wavy. Dry AMD is much more common, occurring when the macula cones degenerate. Sometimes dry AMD turns into wet AMD.

Once dry AMD becomes advanced, no form of treatment can prevent vision loss. However, fortunately for the man who could not read, treatment can delay and possibly prevent intermediate AMD from progressing to the advanced stage. The National Eye Institute’s “Age-Related Eye Disease Study” (the AREDS) found that taking a high-dose formulation of antioxidants and zinc significantly reduces the risk of advanced AMD and its associated vision loss.

The Man Who Couldn’t See Stars

Imagine not being able to see stars. This is the sad tale of a man who could not. This man loved to go out at night and look at the sky when he visited the countryside. He used to find his favorite distant star by scanning the northern sky, and when he spotted its faint glow, he would look off to the side so that he could see it out of the corner of his eye. He always found it fascinating that he could see a dim star better with his peripheral vision than when he fixated it directly.

On one visit, his first in 2 years, he was very excited when he spotted his star. To his great dismay, however, when he looked off to the side, as he had done so many times before, the star disappeared. He had noticed during the preceding year that he was beginning to experience difficulty driving at night. Sometimes he didn’t see cars off in the distance, or cars overtaking from the side. And he seemed to be dazzled for a long time by the headlights of oncoming vehicles. Movies were also becoming a problem. It seemed to take forever for his vision to adapt to the darkness of the theater.

He was also beginning to experience other difficulties with his vision. Just in the previous week he had walked into a table in a restaurant, and several times he had tripped over items that he simply hadn’t noticed. He hadn’t worried too much about these difficulties, because he was having no trouble reading and his vision in bright lights seemed just fine. But not seeing his favorite star out of the corner of his eye really shook him. He was reminded of his father, who in his later years had not been able to drive or read because he had been almost totally blind.

Retinitis pigmentosa (RP) is a family of hereditary diseases characterized by the progressive death of photoreceptors and degeneration of the pigment epithelium. In the most common form of RP, exhibited by the man who could not see stars, the rods are affected before the cones. Therefore, people suffering from this form of the disease first notice vision problems in their peripheral vision and under low-light conditions—situations in which rods play the dominant role in collecting light. In some cases, vision loss progresses slowly and goes unnoticed until age 20 or later. However, the age of onset and rate of progression vary greatly, probably reflecting complex variations in the genetics of the disease. Eventually, visual loss spreads toward the fovea, often leading to total blindness.

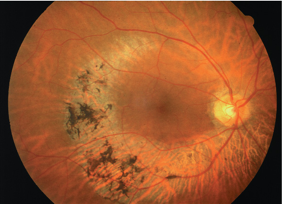

Image 2 shows the fundus of the man who could not see stars. A comparison with the normal fundus pictured in Figure 2.6 of the textbook shows that the most striking difference is the presence of conspicuous clumps of pigment in the RP fundus that have a characteristic shape and are known as “bone spicules.” These bone spicules are the hallmark of retinitis pigmentosa.

Image 2 Fundus of a patient with retinitis pigmentosa. Compare this picture with the normal fundus shown in textbook Figure 2.6. (From Rodieck, 1998.)

When you’re reading this book, you direct your gaze (and your fovea) at the words. But if an elephant were to walk up beside you, you would see it out of the corner of your eye (your peripheral field of vision) and most likely make an eye movement to look at it directly. Luckily, the extent of peripheral vision in intact visual systems is pretty big. How big? You can test the extent of your own visual field by closing your left eye, stretching your arms out in front of you with index fingers raised, and moving your right finger around while you fixate your gaze on the left finger. The points at which you can no longer see the right finger above, below, and to the right and left of the other finger define the limits of your peripheral vision.

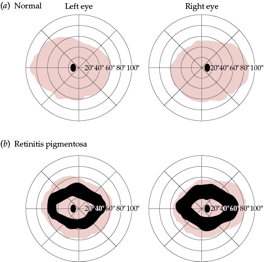

Normal visual fields (Image 3a) are limited by anatomy: the upper, lower, and inside edges are set by the prominence of the eyebrows, cheekbones, and nose, respectively; the outer edge is limited by the abrupt edge of the retina. RP sufferers typically exhibit an overall shrinkage of their visual fields (Image 3b), as well as “ring scotomas,” bands of blindness between the relatively normal central visual fields and the peripheries.

Image 3 Visual fields in (a) individuals with normal vision and (b) the man who couldn’t see stars. The fields are pictured as though we were looking through the back of the patient’s head at the field limits on the retina. Thus, the right eye is shown on the right, and the left eye on the left. The numbers show the visual angles in degrees. The reddish-shaded areas show the outer limits of vision (the size of the visual field). The small black ovals in the center represent the physiological blind spot (due to the optic nerve head). In part (b), note that the outer limits of vision are somewhat shrunken, but more importantly, a ring of blindness (illustrated by the black ring) occupies the middle of the visual field. This ring scotoma is one of the hallmarks of retinitis pigmentosa.

At present, there is no cure for retinitis pigmentosa. Large doses of vitamins A and E evidently alter certain electrical potentials that can be measured from the retina and may slow the progression of RP by a very small amount, but it is not clear that these large vitamin doses actually improve either visual fields or dark adaptation. However, there is hope for people with RP. On June 26, 2000, mapping of the human genome was completed, paving the way for new treatments of genetic diseases. Several genes associated with RP and related diseases have already been identified, and gene replacement therapy has shown promise in mice models (Busskamp et al., 2010).

Glossary Terms

- age-related macular degeneration (AMD)

- A disease associated with aging that affects the macula. AMD gradually destroys sharp central vision, making it difficult to read, drive, and recognize faces. There are two forms of AMD: wet and dry.

- macula

- The central part of the retina that has a high concentration of cones.

- fovea

- A small pit, near the center of the macula, that contains the highest concentration of cones, and no rods. It is the portion of the retina that produces the highest visual acuity and serves as the point of fixation.

- scotoma

- The blind spot in the middle of the visual field.

- retinitis pigmentosa (RP)

- A progressive degeneration of the retina that affects night vision and peripheral vision. RP commonly runs in families and can be caused by defects in a number of different genes that have recently been identified.